(Then Repeat the Process)

In this part of the Contact Centre Manifesto series, we look at how a programme of continuous change and improvement can benefit business culture.

The Problem

Contact Centres Often Have Many Broken Processes

Contact centres are complex environments to operate. Staff often need to have broad knowledge of business practice, computer and telephony systems are varied, and compliance obligations underline every activity.

For these reasons and more, contact centre processes can quickly grow out of touch with customer needs. Call drivers change based on activity in other areas of business, but it’s the contact centre that has to adapt to them.

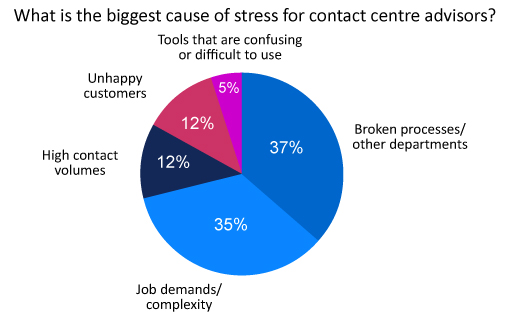

Our poll shows that contact centre advisors are most stressed by broken processes and other departments.

(The poll above was taken from the page: Contact Centre Advisors are Most Stressed by Broken Processes and Other Departments)

Click here for more information on our Top Tips for Fixing Broken Processes article.

Broken Processes Tend Not to Get Fixed

Change management is complex. Managers need specialised skills and tools in order to guarantee that their efforts have benefit. If approached without detailed planning, changes might easily create more problems than they solve.

Some leaders don’t have a totally clear understanding of the major pain points for customers and staff, even when they’re trying hard to find out. It is often the loudest voices who get their opinions heard, which is why a fair and structured approach is needed.

“What we found before my team became a real presence in customer service was that the ops managers would engage in change activities but they didn’t really have a process and didn’t know the steps to follow.

“We were keen to separate CHIMP (Change and Improvement) from ops managers, so we could focus on change and they could focus on looking after their teams.” George Frost, Senior Change and Improvement Manager at OVO Energy

Change Projects Are Often One-Off

Continuous change and improvement should ideally be… continuous. The work of honing customer experience is never complete.

Resource shortages often mean that even those businesses that want to stay mobile are only willing to tackle change on a project basis a few times a year. This does not create enough scope for meaningful change.

Perhaps the deeper problem, though, is that routinely starting and stopping projects is inherently inefficient – the best improvement plans are ongoing.

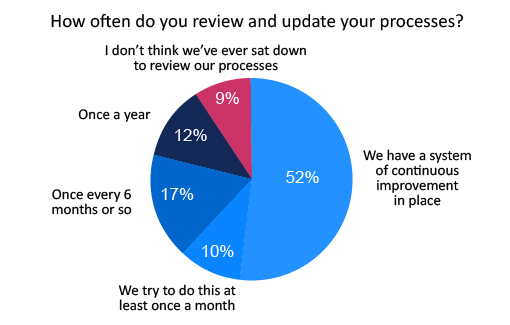

As the results of our recent survey show, only half of contact centres are engaged in continuous improvement.

(The poll above was taken from the page: Over Half of Contact Centres Have a Continuous Improvement System to Update Processes)

Nobody Has the Time to Implement Change

Unlike most workforces, contact centre agents are always ‘on’. That means frontline agents being available for calls, and supervisors keeping track of performance.

The same is true at the upper management level, albeit on a different scale. This creates the problem that an environment that needs to be adaptable rarely finds the time to adapt.

Change and improvement projects require a lot of planning before they even reach implementation. There are rarely people in the contact centre who can give these kinds of projects the time needed.

What Can You Do About This?

Make Change and Improvement Somebody’s Job

For change to be a meaningful part of business, it must have resources dedicated to it. This means a person, or ideally a team, whose role is to locate potential gains, create a timescale for implementation, and communicate them to the wider staff.

Communication is a key part of what this team should handle, explaining change and acting as a point of contact for anyone who needs more information. Change will directly impact the working lives of staff, so a clear communications remit – or a solid relationship with the comms team – is essential.

Similarly, a change and improvement team also exists to receive ideas from the staff.

There is only ever a certain amount of change that will be practical, and a certain amount of time to arrange it. It’s a specialised skill set, best performed by people who have the ability to focus on it entirely.

“Organisations that are serious about change and improvement need to be brave and make it somebody’s job, which can be a leap of faith. That person needs to have training as well as a very ordered mind and a structured approach.

“They need a solid understanding of the key drivers, and to prioritise based on that with a structured method like a prioritisation matrix. If you’re not planning like this, then all you can do is firefight or deal with whatever problem was first.” George Frost.

How Should You Identify Areas of Change?

Obviously, the first thing to do is gather information about the kinds of problems you face. This data can gradually be refined through a variety of processes, but to get started you just need to know what drives calls and complaints.

There are a lot of great data sources in the contact centre, each with its own strengths and weaknesses.

1. Ask Your Contact Centre Staff

Pros:

Staff at every level will have their own insights into process and customer experience. In particular, frontline staff can get a very good read on customer disposition, often the most nuanced understanding of impact.

Supervisors know which issues affect their teams, real-time managers understand volume and call trends, and so on.

If you need a broad view of day-to-day experience, asking staff directly is a good place to start.

It’s also good for morale when staff feel that they can contribute to change.

“The role of the agent here is not just to complete transactions but to gather and analyse information. In this sense, agents can be an intelligent cog in a reactive, organic business strategy. This is especially plausible with agents working on social media, as they have the free rein to dig into problems a bit more.” Peter Massey, Managing Director at Budd.

Cons:

Customer-facing staff will be most aware of the issues that trigger the biggest responses – but these aren’t always the biggest problems.

For example, imagine a flawed billing process that inconveniences customers and leads to one angry contact per week. This could easily be what agents remember when asked about potential improvements.

However, they might not think about the five calls per day clarifying store opening hours. A closer look at the data may reveal that five minor complaints per day account for more dissatisfaction than one big complaint per week.

2. Analyse Wrap-Up Codes

Pros:

This is usually a very big data set that can show you broad trends in call drivers.

You can look deep into the trends and see if they align with real-world events. For example, website issues might lead to an increase in calls for basic details like store opening hours.

Click here for more information on our Call Centre Abbreviations to Speed up Wrap Time article.

Cons:

While wrap-up codes will tell you what topics drive calls, they can’t often tell you much about the underlying issues that cause them.

Agents may also leave notes, but this is usually a non-standardised data set that will be much harder to analyse.

For wrap-up codes to be very reliable, agents must be incentivised to record accurately, which means making input adherence a part of call scoring.

3. Listen to Calls

Pros:

Listening in can give you a feel for the emotional impact of the issues you look at. You also get to hear how the process works in action, clarifying where exactly the problem is.

You might even find that customers have the answer and express how the process could be more convenient for them.

Cons:

It’s hard to get a representative sample of calls without quite a lot of preparation. If you take the issues that come up from random call sampling as the issues you most need to deal with, you might not get a great idea of your priorities.

Listening to calls is also very time consuming.

4. Use Interaction Analytics

Pros:

Speech and text analytics can refine your understanding of other data. It’s used to link trigger phrases (negatives like “let me speak to your manager” and positives like “you’ve been very helpful”) to the contact outcome and wrap-up codes.

Speech analytics can present data to the end-user in a variety of formats so that patterns become highly accessible.

Cons:

Interactions analytics can be expensive to start and hard to use, especially with speech. Ultimately, the result will only be as good as your ability to use the technology.

This means knowing which words and phrases to look out for, and understanding what they mean in context.

Analytics are not ‘plug and play’ – you will need a reasonable understanding of call drivers already, and a strategy for how you will use the software.

5. Review Customer Surveys

Pros:

Rather than going through interaction data, you can just ask customers what could be better.

Direct feedback can be obtained in a number of ways, and has become relatively cheap. As a fringe benefit, you get to show customers that you are interested in improving your service, and you can follow up with any that return very low scores.

Cons:

Feedback tends to be outside of the average experience, either high or low. That means it’s not totally representative in the way that you might expect, although that obviously depends on how your data is collected.

It’s important that your surveys are designed with a clear objective and give customers the maximum opportunity to express themselves. Otherwise you might find out that customers are unhappy without finding out exactly why.

Overall, it’s clearly best to employ a balanced combination of techniques. Staff feedback and wrap-up codes can help to identify big call drivers, and listening to select calls from those groups will establish the common themes. With this search criteria for interaction analytics you can understand the outcomes of these issues and get some idea of the level of impact.

It is also important that you maintain a clear understanding of why you are making these changes and what the impact will be beyond fixing an immediate problem. This is why any proposed changes need to undergo serious and nuanced analysis before implementation, to establish whether there may be unintended consequences.

How Do You Start Making Changes?

There are probably no contact centres that wouldn’t be able to find some areas to improve. But there are many that would have trouble deciding what to tackle first.

One of the major issues that any business faces when it attempts to improve is the limited scope of their resources versus the huge number of ideas.

Next, we are going to look at some of the methods that can help project owners focus their energy on worthwhile goals.

Identify Your Top Three Issues

Enthusiasm for positive change is great, but some restraint is recommended. Without restraint, you risk taking on too many projects or moving from one to another without making significant advances.

A better idea is to select a manageable number of issues that will get your full attention until you can safely say they no longer need constant attention. Limiting the number of projects you take on has a few advantages. Aside from being able to give them your full focus, taking on just three projects at a time will force you to think about what your real priorities are.

It also allows people outside of your team to keep abreast of what you are working on. As we’ve discussed, change and improvement projects should in some way involve everyone within your business. This is much more achievable if there are only a small number of goals at any one time.

How to Use a Prioritisation Matrix

A prioritisation matrix is a method for weighing the relative benefits of a project as well as deciding what your ultimate goals should be.

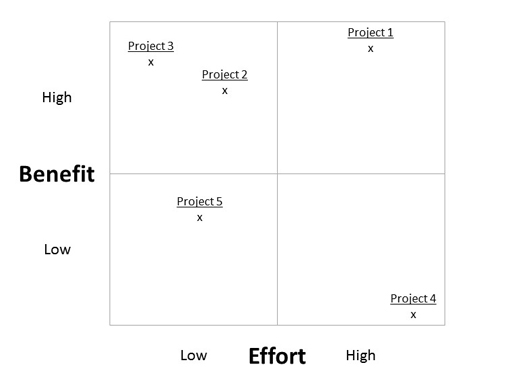

Here’s an example of a very simple benefits vs. effort matrix. It’s useful when teams have far too many ideas and need to eliminate some.

In a simple 2×2 grid, mark the position of your potential projects by estimating the effort that would go into them and the reward you would reap.

Where benefits are high and effort is low, you find the projects that are most worth taking on, especially when your improvements scheme is new and you need to demonstrate value.

“We paid attention to quick fixes because that helps with buy-in – individuals can point to something and say that they helped to fix that.” Ruth Mercer, Operations Manager at Hughes Insurance Ltd

This representation of the data is highly generic and can’t work as the backbone of your scheme on its own. But as a way to organise your thoughts, or get across the core concept to your team, this is a useful exercise.

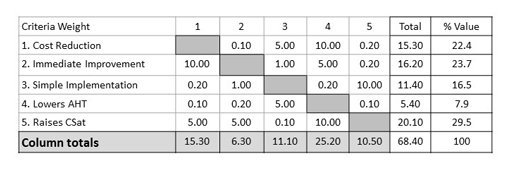

A much more sophisticated type of prioritisation matrix starts with goals instead of individual projects:

Here we see 5 areas that a change and improvement team might want to focus on. Each criterion is measured and awarded a score in relation to the others.

10.00 – Much higher significance

5.00 – Higher significance

1.00 – Equal significance

0.20 – Lower significance

0.10 – Much lower significance

This can be arranged quite simply in a spreadsheet. The output in this example is that the principle interest is for projects that raise CSat. Projects that focus on lowering AHT are not a priority.

The process can be repeated with the various project proposals compared against one another on how well they accomplish CSat gains.

This is useful because it can equalise the opinions of the entire team. Rather than the loudest person convincing the rest, all input can be collated and averaged, preventing pet projects from going ahead first.

Pareto Analysis

Pareto analysis draws on an idea that many operations staff will be familiar with – the Pareto Principle.

Simply put, the Pareto Principle states that 80% of outcomes can be linked to 20% of causes. In practice, that could describe 80% of a business’s income coming from 20% of its customers, or 80% of an office’s workload being handled by 20% of its staff. Or in this case, the 20% of process issues that cause 80% of problems.

Acknowledging the biggest problem areas can help focus change strategies on the areas that need it most.

Call drivers are plotted on the X axis against call volume on the Y axis. Alternatively, call volume could be replaced with call cost or number of complaints – it depends on the project’s focus.

Cumulative call volume is plotted over the top. The point at which this line reaches 80% indicates which issues are part of the ‘vital few’.

This establishes where the majority of problems arise and links them back to relatively few individual issues. These are the issues that require the most attention.

Root Cause Analysis

Once you have established which issues you are going to target, the next step is to understand why they occur.

This might not be as straightforward as it sounds. The surface-level data might indicate a cause that is itself a symptom of the underlying fault.

Consider a domestic example: You notice that your home energy bills are very high. You want them to be as low as possible, so you make some enquiries and switch energy supplier. Job done?

Well, maybe not. Perhaps your house is cold because there’s no insulation in the attic. Your bills are high because of the heating requirements, but the expense is just a symptom. In reality, the root cause of your problem – high energy bills – is not the price of energy but the inefficiency with which you’re using it.

Root causes analysis basically involves asking ‘Why?’ until you get to the lowest level of cause.

My energy bills are too high. Why? Too much energy is used for heating. Why? The building gets cold. Why? It doesn’t retain the heat. Why? It is not well insulated. Why? Well… good question. Let’s get some more insulation.

Four Stages of Root Causes Analysis

1. Identify the Problem

Define the issue you want to resolve, and define it precisely. In the contact centre, low CSat is a problem, but it’s a very general problem with a lot of causes. A related but more specific problem might be that there is very low satisfaction around delivery timescales.

2. Ask Questions

The first question should be ‘is this really a problem?’ Are our delivery timescales outside the industry benchmark or our own projections? Are they outside what we as consumers would expect?

If so, what causes this? There are generally three categories or error: technology, personnel, and process. Is old technology hindering staff? Are staff under-trained?

If these delays are the result of slow processes, what makes the processes slow?

Bear in mind that in a complex business environment there can be more than one major cause contributing to an effect. In this example, orders taken over the phone might be manually processed in batches at the end of the week, contributing to the delay. But if the warehouse team also have a sluggish process, the problem cannot be solved by only tackling the issue on your end.

In both questions, the obvious question is ‘why are orders handled this way?’

3. Create a Process Map

This can demonstrate the current process and highlights the particular issues with it. It also enables you to see what a new process could look like.

There’s no point replacing one broken system with another, so you need to test the idea as rigorously as possible. Show the new process to anyone who will be affected by it and see if they can demonstrate a way it is flawed.

4. Implement the New Process

Implement the process and analyse the results. If your initial problem was well defined, you should have some obvious criteria to measure, and you can establish if this has the intended result.

Is the process now more simple? Does this decrease delays? Is satisfaction higher as a result?

Six Sigma and Lean Approaches

Both of these methodologies use root cause analysis to evaluate process performance with an aim of increasing efficiency. They are highly effective for designing or developing single processes to maximum performance.

Six Sigma was developed for the manufacturing industry, so some of its guidance is hard to apply to customer service and sales. Broadly, the key focus is on reducing the number of defects in a process. As Philip Crosby once said, “the definition of quality is conformance to requirements.”

This practice has two sub-methodologies, DMAIC and DMADV, which are used to evaluate existing processes and test new methodologies.

DMAIC – Define, Measure, Analyse, Improve, Control

DMADV – Define, Measure, Analyse, Design, Verify

Individual contact centre interactions don’t compare easily with machine-produced products. There will always be a level of variation in how different agents perform their tasks, and it is debatable whether this is something leaders should try to control too much.

Of course, human-to-human interactions are only one small part of what the industry does. There are numerous automated processes that are handled in an exacting and specific way every time. IVR, call routing and the queueing experience are all examples of processes that are uniform and can be improved through a structured approach like Six Sigma.

Lean is more customer-centric and focuses on removing waste. It does also place emphasis on reducing variation, but perhaps more significant for the contact centre is its focus on the waste involved in putting stress on people or equipment. As the levels of staff attrition can attest, this kind of waste is extremely expensive in contact centres.

Both of these approaches take a reasonable investment of time to get familiar with. However, as is the case with every aspect of change and improvement we have covered, an upfront investment of time will lead to far more significant change.

This article forms part of The Contact Centre Manifesto series

The following ideas have been discussed with the industry experts pictured below:

[left to right] George Frost, Senior Change and Improvement Manager at OVO Energy, Peter Massey at Budd, Ann-Marie Stagg at the Call Centre Management Association (CCMA), and Ruth Mercer, Operations Manager at Hughes Insurance Ltd

Author: Rachael Trickey

Published On: 22nd Jun 2016 - Last modified: 27th Nov 2023

Read more about - Customer Service Strategy, Contact Centre Manifesto, Editor's Picks, Peter Massey