Dave Salisbury reviews the academic research and explores how contact centre leaders can best harness technology in creating a culture of adaptability.

Technology is a tool, like a hammer

The role of technology is to act the neutral part in the human–work relationship. Technology is a tool, like a hammer, designed for a specific purpose embodying potential for good or ill, delivering a specific role, and serving a specific function. Technology is not positive or negative and possesses no value matrix beyond addressing the concern, “does technology fill the role it was designed for or not?” (Budworth and Cox, 2005; Ertmer, 1999; Ropohl, 1999). Technological philosophy, detailed by Ropohl (1999), provides greater details into the underlying core issues leaders and organisations face daily when merging technology and people together. Yet, always in application do we find managers attempting to make technology more than what technology can ever be, the neutral variable in the human–technology work relationship, while thwarting culture and other organisational changes.

The automatic dishwasher is an example: if the dishes go in dirty and come out dirty, the blame is with the technology instead of the human interaction in the technology–work relationship.

The system is running slow

I was on a call to customer service recently and heard no less than five times in a 10-minute phone call, the “system is slow”, the “computer is not working right”, or some other similar excuse from the agent for not being able to answer questions from the customer. How many times has human resources heard: “the car wouldn’t start”, “my GPS gave me wrong directions”, or, my personal favourite, “the alarm clock failed.” The technology is not at fault as the neutral variable; human interaction with the technology is where the fault lies.

Application of technology to leadership and organisations may be summed by Wixom and Todd (2005) as they quote Fishbein and Ajzen (1975) for the specific principle espoused by Trist (1981) and applicable here, “For accurate prediction, beliefs and attitudes must be specified in a manner consistent in time, target, and context with behavior of interest” (Wixom and Todd, 2005, p. 89). Virtual and non-virtual teams are connected by the specific behaviours of those being led; the attitudes of the users predict beliefs and flow into production, especially into call centres and other frontline/customer-facing positions. Technology brings leadership into possibility, but the potential cannot be realised unless the leader knows how to harness negative beliefs, core out the actual problem, address user concerns, and then redirect the negative into either neutral or positive productivity.

Empowering users with 360-degree feedback

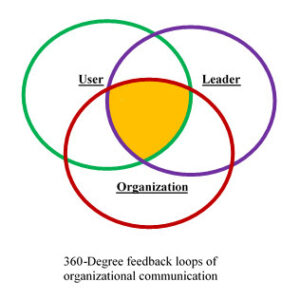

The answer to leaders needing to harness user beliefs is found in proper communications aided by technology, as detailed by London and Beatty (1983). Empowering the user with 360-degree feedback, empowering the leader with another channel for 360-degree feedback, and operating a third channel for the organisation in 360-degree feedback places the user in the driver seat to improve their technology beliefs and attitudes. Ropohl (1999) and Omar, Takim, and Nawawi (2012) combine to complete the puzzle in addressing how technology applies to leadership and virtual teams by underscoring the people element in the technological equation. Omar et al. (2012) claim,“…Technological capability refers to an organisation’s capacity to deploy, develop and utilise technological resources and integrate them with other complementary resources to supply the differentiated products and services. Technological capability is embodied not only in the employees’ knowledge and skills [combined with] the technical system, but also in the managerial system, values and norms” (Omar et al., 2012, p. 211).

As the image reflects in the convergence of the three channels of 360-degree feedback, the power of communication is enhanced by the technology employed as a neutral variable in the human–technology work relationship. If technology fails, the relationships in the channels remain and the relationships are not separated or closed. When discussing flexibility and adaptability in organisations, clearly understanding the roles of technology and communication empower the combined user, leader, and organisation relationships.

Technology not thought through is “Organisational Cancer”

The leader and organisation need to understand and develop these principles to harness the innovative power of the human element where technology interacts with the human–work relationship. If technology, especially technological improvement, is not thought through, planned, discussed, and elevated, Dandira (2012) claims the result is “Organisational Cancer”. The power of technology as a force multiplier to unleash the power of humans cannot be understated, but the flip side of the technological coin is that if technology is not handled correctly, the negative aspects are as large as the positive aspects. Toor and Ofori (2008) detail how leaders need to understand and embody the differences between managers and leaders to contribute fully to the technology implementation and daily use in production. If leaders cannot lead physical teams, they will never understand virtual teams, where technology must be understood more completely, and managers need not ever apply as the mindset is not conducive to creating success in the human–technology work relationship.

Promised technology “better than sliced bread”

A recent technological change was heralded, marketed, bragged, and positioned to the stakeholders in a company as akin to being better than “sliced bread”. The new system was discussed for three years before images of it began to be floated. Everything was prepared to have the technology play a more flexible and vital role in the organisation. The problem was that managers and programmers implemented the technology instead of users and leaders. User interfaces were ungainly, illogical, and made no sense in the completion of the users’ work processes. More specifically, the impact for every single process and procedure in the current technology was not considered and revamped during the roll-out of the new system. The result was chaos among users, failure to deliver the promised products and services, and a customer service disaster. Early in the roll-out of the technology, managers directing it were alerted that processes and procedures needed to be revamped, and the user was being left behind in how the system was “supposed to work”, resulting in compounded chaos, increasing customer dissatisfaction, and further diminishing the company’s reputation. The managerial response was to “sit and wait” for the programmers to finish building the system and changing the technology to “fit”. Where a leader was needed, a plethora of managers existed, and they actively worked to make the problems worse for the end user, the customer, and the other managers.

Words, actions, repetition and the passage of time

Creating a culture follows a basic set of principles, namely, the example of the leaders, including their words and actions, followed by repetition, and the passage of time (Tribus, n.d.). Tribus (n.d.) specifically places the core of culture in the example of the leaders, regardless of whether the organisational leader is a leader or a manager as evidenced by action and word. To create a culture specific to adaptability, several other key components are required, namely, written instructions, freedom, and two-directional communication in the hierarchy (Aboelmaged, 2012; Bethencourt, 2012; Deci and Ryan, 2000; Kuczmarski, 1996 & 2003). Two-directional communication has been warped into 360-degree communication. Regardless of name, the input from the workers and the customer is more critical than the voices of managers to organisational excellence.

Alvesson and Willmott (2002) add another component to this discussion. As the organisational culture takes hold of an individual employee, the employee begins to embody the culture, for good or ill, in their daily interactions, both personally and professionally. This hold becomes an identity, adding another level of control from the organisation over the employee, binding them to the organisation. The identity control becomes a two-edged sword because the employee will form loyal opposition that can be misinterpreted as intransigence, and the loss of that employee causes other employees to question their identity and the organisational culture. More to the point, the changed employee becomes habitualised into the current culture and then hardens into intransigence when changes are needed to help the organisation survive.

Setting clear goals and defining the vision

To create a culture attuned to adapting, the organisational leader needs to communicate, be seen exemplifying the organisational culture, and build that culture one employee at a time, until the changed employees can then begin to sponsor other employees in the organisation’s new culture. The organisational leader must set clear goals, define the vision, and obtain employee buy-in prior to enacting change, then exemplify that vision after the change (Deci and Ryan, 1980, 1985, & 2000) while remaining open to the possibility of a need to change direction if indicated. Key to this process is Tribus’ (n.d.) [p. 3–4] “Learning Society” vs. “Knowing Society”. The distinction is crucial. The organisational culture must be learned and the process for continually learning honed and promoted to protect the culture while adapting to variables, both internal and external. Learning societies know change occurs because of new thinking and inputs, and they remain adaptable to that change as a positive force in improvement. Knowing societies remain afraid of changes due to the fear of losing perks, benefits, or personal power, and they actively thwart change at every turn, usually while preaching the need to change.

Technology as a neutral force

To be clear, technology is a neutral force and can neither be a positive or a negative in an organisation. The need for leaders cannot be overstated as the driving force in organisational change or simply day-to-day leadership. Leaders must be seen and heard living the organisational culture. If, and when, changes are required, leaders must listen to users, customers, and the managers, but the weight and value of each of these is not the same and should never tilt in favour of the managers. Finally, if the organisation needs to adapt, it must provide employees in frontline/customer-facing positions with freedom to act and the technology to record the actions, supported by back-office processes and procedures that respond to the frontline, not the other way round.

Dave Salisbury

A spirit of freedom and adaptability

With the “dot com” bubble burst in 2000, the world of business changed dramatically. As more baby-boomers leave the workforce and are replaced with millennial workers, the business culture is going to change more. To adapt, the engaged and determined business leader needs to embody a spirit of freedom and adaptability in the business culture, in the processes and procedures that define “work”, and in the customer relationship (internally and externally) or the business will continue to fail, struggle, and breed chaos.

With thanks to Dave Salisbury, Operations and Customer Relations Specialist

References

Aboelmaged, M. (2012). Harvesting organizational knowledge and innovation practices: An empirical examination of their effects on operations strategy. Business Process Management Journal, 18(5), 712-734.

Alvesson M, & Willmott H. (2002, July) Identity regulation as organizational control: Producing the appropriate individual. Journal Of Management Studies 39(5):619-644. Available from: Business Source Complete, Ipswich, MA. Accessed July 27, 2014.

Bethencourt, L. A. (2012). Employee engagement and self-determination theory. (Order No. 3552273, Northern Illinois University). ProQuest Dissertations and Theses, 121. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/1294580434?accountid=458. (prod.academic_MSTAR_1294580434).

Budworth, N., & Cox, S. (2005). Trusting tools. The Safety & Health Practitioner, 23(7), 46-48. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/201021810?accountid=458

Dandira, M. (2012). Dysfunctional leadership: Organizational cancer. Business Strategy Series, 13(4), 187-192. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/17515631211246267

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1980). The empirical exploration of intrinsic motivational processes. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 13, pp. 39–80). New York: Academic Press.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. New York: Plenum.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11, 227–268.

Ertmer, P. A. (1999). Addressing first- and second-order barriers to change: Strategies for technology integration. Educational Technology, Research and Development, 47(4), 47. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/218016186?accountid=458

Kuczmarski, T. (1996). What is innovation? The art of welcoming risk. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 13(5), 7-11.

Kuczmarski, T. (2003). What is innovation? And why aren’t companies doing more of it? What Is Innovation? And Why Aren’t Companies Doing More of It?” 20(6), 536-541.

London, M., & Beatty, R. W. (1993). 360-degree feedback as a competitive advantage. Human Resource Management (1986-1998), 32(2-3), 353. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/224341530?accountid=458

Omar, R., Takim, R., & Nawawi, A. H. (2012). Measuring of technological capabilities in technology transfer (TT) projects. Asian Social Science, 8(15), 211-221. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/1338249931?accountid=458

Ropohl, G. (1999). Philosophy of Socio-Technical Systems. Society for Philosophy and Technology, 4. Retrieved June 29, 2014, from: http://scholar.lib.vt.edu/ejournals/SPT/v4_n3html/ROPOHL.html

Toor, S., & Ofori, G. (2008). Leadership versus Management: How They Are Different, and Why. Leadership & Management in Engineering, 8(2), 61-71. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)1532-6748(2008)8:2(61)

Author: Dave Salisbury

Reviewed by: Jonty Pearce

Published On: 9th Nov 2016 - Last modified: 16th May 2024

Read more about - Customer Service Strategy, 360 Feedback, Culture, Dave Salisbury, Team Management